I had just

been initiated into Transcendental Meditation and was very enthusiastic about

it. So when during a train journey in India I found myself sitting beside a

saffron-clad Hindu monk, i started a conversation with him hoping he would have

some insights to share. The swami, who happened to be an ayurvedic physician too, instead began a lengthy discourse on the

Indian system of medicine while I impatiently looked for a chance to interrupt.

When he stopped for breath I pressed in my favorite topic.

I had just

been initiated into Transcendental Meditation and was very enthusiastic about

it. So when during a train journey in India I found myself sitting beside a

saffron-clad Hindu monk, i started a conversation with him hoping he would have

some insights to share. The swami, who happened to be an ayurvedic physician too, instead began a lengthy discourse on the

Indian system of medicine while I impatiently looked for a chance to interrupt.

When he stopped for breath I pressed in my favorite topic.

"Swamiji, what do you think of Transcendental

Meditation?"

He replied gravely, "It is a serious disease but ayurveda has very good medicines for it." Then he continued about the cases of tuberculosis he had treated.

It is possible that in the din of the running train he misheard me. Much more likely, his ears did catch my words correctly, but so involved was his brain at that moment with medical matters, that any sensory input presented to it got processed that way. In other words he was experiencing what psychologists would call a perceptual set or more informally a "mindset."

Trivial as it is, this

incident could be a pointer to some of the more serious problems facing the

human species as a whole. Do notions in our minds sometimes make us perceive

things differently from what they really are, leading to erroneous judgments

and actions? If so, can we do anything about it? Before going further, let us

consider the graphic below.

What does it appear to be?

Most people would first spot the cup in the center or the human faces framing it. But (try as we can) we cannot see

the cup and the faces at the same moment –– though we can quickly flip back

and forth between them. This is because the picture is only suggestive and it

takes some organized effort on the part of the brain to perceive it as a cup or

the human faces. Once the brain has become "set" in seeing the cup,

it cannot see the faces and vice versa. It may also make us forget another fact

–– the cup and the faces are purely the creations of our minds.

What does it appear to be?

Most people would first spot the cup in the center or the human faces framing it. But (try as we can) we cannot see

the cup and the faces at the same moment –– though we can quickly flip back

and forth between them. This is because the picture is only suggestive and it

takes some organized effort on the part of the brain to perceive it as a cup or

the human faces. Once the brain has become "set" in seeing the cup,

it cannot see the faces and vice versa. It may also make us forget another fact

–– the cup and the faces are purely the creations of our minds.

What happens in the instance

above is that our senses have a straightforward job to just capture outside

stimuli such as light and sound which they convert into electrical impulses and

feed to the brain. The brain initiates a checking and cross checking process.

Within a split second the new information is compared with the already stored

memory bank from past experiences. The object is thus identified and the brain

sends commands to the rest of the body to make appropriate responses. The

accuracy of this identification and the appropriateness of our response depends

on how correctly the comparison has

been done.

Though this process is

practical enough for everyday life, there are occasions when it can hamper us

from experiencing and reacting to reality.

For instance, a mindset can

make us mistake a white shirt on a clothesline for a ghost. All that the eye

picks up may be a fluttering flash of white. It is the brain that goes through

its "ghost database" and plumps up the stark visual input with those

extra qualities appropriate for a ghost. The person "sees" the ghost

and panics.

Creativity versus mind set

The stimulus-response nature

of mindsets also affects the higher faculties of the brain by pre-empting

creative thought sometimes under the guise of common sense. If Isaac Newton had

such common sense perhaps he would have just eaten the apple that fell on his

head and resolved never to sit under laden apple trees again. Similarly, young

Albert Einstein wouldn't have pestered his elders with naive questions about

time and space.

Fortunately Newton and Einstein had the depth and freedom of

perception far beyond common sense and mankind has been the gainer. In fact

Einstein once recapitulated with endearing humility how he came upon his theory

of relativity. "My intellectual

development was so slow that by the time I started wondering about space and

time those of my age had already outgrown it. Naturally I could go deeper into

these than they could at a younger age." Outgrown is correct. We do

become more prone to mindsets as we grow older.

In creative people mindsets

occasionally get resolved through a dramatic process called

"insight." The person thinks and thinks about a problem for days and

weeks and despairs. Suddenly in a flash the solution appears, often so simple

that he wonders why he never thought of it before.

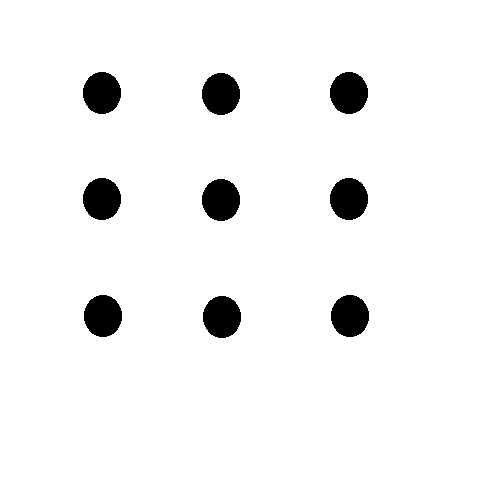

Here's a little test. Try

joining all the nine dots by four straight lines without lifting the pencil off

the paper once you start. If you are like most of us, you would have spent an

amazing amount of time trying to solve the problem with lines that stay within

the imaginary square formed by the group of dots. That square is the mind set. Once that is got over with, the rest is

quite easy. It is this ability to overcome the automatic influences of past

experiences that makes creativity possible. The solution is at the end of this

article.

Here's a little test. Try

joining all the nine dots by four straight lines without lifting the pencil off

the paper once you start. If you are like most of us, you would have spent an

amazing amount of time trying to solve the problem with lines that stay within

the imaginary square formed by the group of dots. That square is the mind set. Once that is got over with, the rest is

quite easy. It is this ability to overcome the automatic influences of past

experiences that makes creativity possible. The solution is at the end of this

article.A famous mind-set victim

Too much scholarship in one

direction can lead to mindsets, a potential pitfall for a seeker of truth,

whether a scientist or a philosopher. Oddly, the greatest psychologist of the

20th century, Sigmund Freud, stumbled into it. Freud's brilliant theory of

psychoanalysis had won him many disciples, thrilled with this new adventure of

the mind. However, by and by he grew so fond of his theories that he found it difficult

to tolerate significant improvements in them and started expecting his students

to believe his views like religious dogmas. Fortunately Freud's followers too

had bright, enquiring minds which permitted psychoanalysis to grow and branch

off instead of getting fossilized.

|

| Freud on TIME cover at the height of his popularity in the 1920s. |

The fact is that mind-sets

affect us much more than we realize. Many can be triggered to very early childhood.

Origins obscured, we may feel, think and unwittingly behave under their

influence assuming we are being rational.

Among the deepest, earliest

and strongest of such mindsets are our perceptions of what we are. We form such

naïve perceptions during childhood –– even form a life plan! –– and spend the

rest of our lives living up to them, as if under their spell. This is the basis of Transational Analysis (TA), founded by Eric Berne who explained the whole concept in his best seller "Games People Play". TA offers a good explanation of why some people are consistent winners, some others consistent losers and still others seem to change their orientation drastically in midlife, as if under a strange spell. TA gives rational explanation for "fate." Our fate is not written before our birth. We ourselves write it as small children and then forget about them, but still follow them, spellbound. TA calls our childhood mental programming which relentlessly leads us to a preplanned fate, our "life script", which we achieve through our everyday actions by playing constructive and destructive "games" over and over again. Enacted repeatedly, these games powerfully reinforce our mind-sets about ourselves, binding us more and more to our self-composed fate.

Bound down by intense feelings these deep mindsets are the hardest bugs to remove––even to find. We may have to dig deeply down to their roots and weed them out. TA tries to do that by analyzing our everyday interactions with others and give suggestions to modify them so as to change our "script." While TA does a good job of identifying them it is not nearly as successful in removing them. Why? Due to a sad truth: *the vast majority of people who suffer, deep down, do not want to change. They want to remain with their mind sets.*

Bound down by intense feelings these deep mindsets are the hardest bugs to remove––even to find. We may have to dig deeply down to their roots and weed them out. TA tries to do that by analyzing our everyday interactions with others and give suggestions to modify them so as to change our "script." While TA does a good job of identifying them it is not nearly as successful in removing them. Why? Due to a sad truth: *the vast majority of people who suffer, deep down, do not want to change. They want to remain with their mind sets.*

Our daily interactions are mostly with other people. This causes mutual reinforcement of each others' mindsets. This gets spread over to the larger society, which plays its role by reinforcing mindsets, many of them destructive. If everyone around us keeps perceiving and

thinking the way we do, we get added confirmation that we are right. This is

how social evils like caste system and sexism still linger on in spite of all

scientific evidence to the contrary.

Incidentally, another myth

created by overzealous democrats is “everyone is equal.” The error of social

mindsets such as caste in India is that they stifle individual potential by

assuming that each person is fit only for a prefixed duty in life. Over the

centuries this caused an enormous wastage of talent and is the main cause of

the backwardness of South Asia.

One important reason for the

tenacity of such social evils is that they facilitate people in power.

Politicians and religious leaders are quick to emphasize them to motivate

people in the direction they want. Trifling with such emotion-charged mindsets

can be lethal as history has proved time and again.

Mindsets are Not Always Bad!

Despite the havoc they

wreak, mindsets do have some important functions and help our survival

individually and socially. Social mindsets give stability and direction to

society. It is when stability turns to rigor mortis and direction a blind

one-way, it would be time to examine the relevance of the mindset which caused

it. Intelligent vigil and self-examination help, by giving us the freedom to

choose what to keep and what to discard.

At personal levels too,

mindsets are not that bad. They get us through the routine chores of life with

minimum time and energy (habits) and help us avoid the plight of the centipede

that

Wondered which leg came after which

And so lay distracted in a ditch.

Wondered which leg came after which

And so lay distracted in a ditch.

An everyday example of the

usefulness of mindsets is in front of us right now––the ability to read fast.

If you are not so sure, stare at any long word on the screen for a few minutes.

You may find the word slowly losing its meaning and becoming a jumble of letters.

Staring at an individual letter can cause the letter to start to look

unfamiliar. (Incidentally, the more

familiar the word and older you are, the more time it would take for the

meaning to disappear.) This happens because we have learned to associate a

word with an idea (often a picture), an association which becomes increasingly

persistent as we grow older. The letters which constitute the word act as a

combined trigger to retrieve the idea from the filing cabinets of our brains.

Thus we can perceive either the letter, or the idea, but NOT both at the same

time –– just like that picture of the cup and the faces!

Had we no such mindset, we

would have to mentally trace the shape of each letter, then assemble them into

a word, then search for its meaning ...

… and it would take weeks to

read this.

This work (text only) by Sajjeev Antony is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

No comments:

Post a Comment